One night in 1957, drummer Art Taylor failed to show up for a Thelonious Monk gig, and a relative unknown sat in his place. Over the next six decades, the promising sideman would evolve into an extraordinary jazz bandleader and composer. Stephen Paul Motian (1931-2011) was born in Philadelphia and raised in Providence, Rhode Island, the son of Armenian immigrants from Turkey. Paul grew up poor and became something of a “juvenile delinquent”— he was arrested 3 times before the age of thirteen.

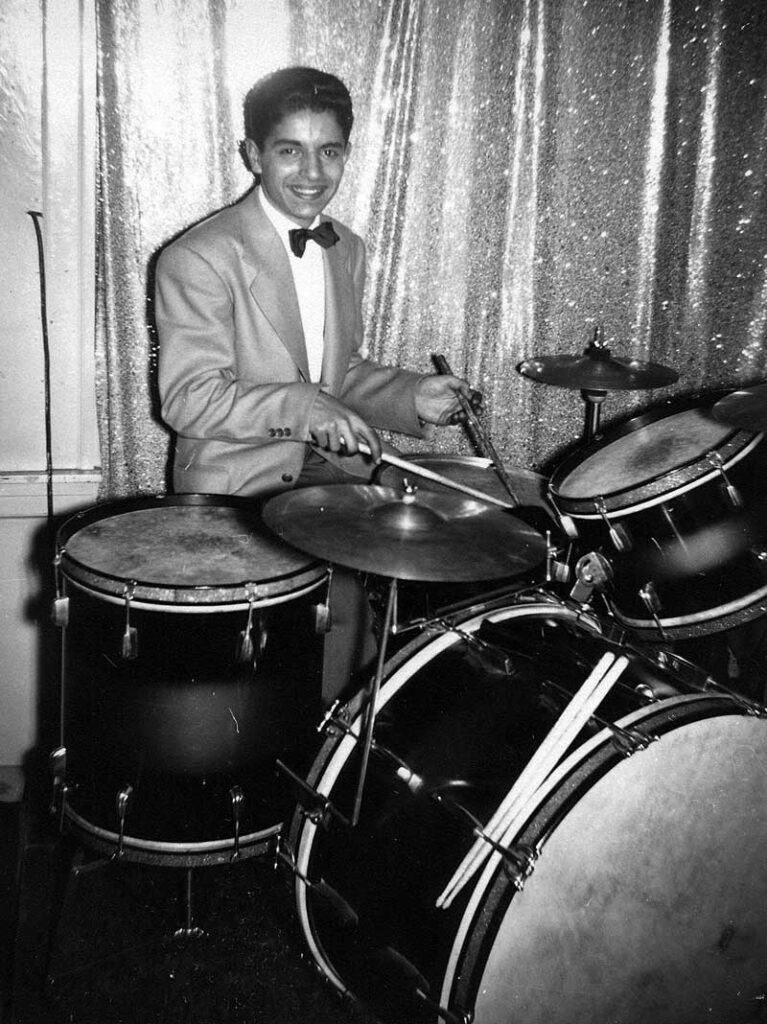

At the age of twelve, he had his first drum lesson. Later in life, he would credit music with keeping him both alive and out of jail. While in high school, he began playing with local swing bands. He then joined the Navy and began performing in a Naval School of Music Unit Band. He was fortuitously stationed in Brooklyn prior to his discharge in 1954, and called New York City home for the rest of his life. Immersed in the 1950s New York jazz scene, he began jamming with musicians throughout the city while absorbing the performances of idols like Art Blakey, Max Roach, and Philly Joe Jones.

Throughout the 1950s and 60s, Paul played with a staggering number of musicians, including Lennie Tristano, Mose Allison, Oscar Pettiford, Stan Getz, Zoot Sims, Paul Bley, Lee Konitz, and Charles Lloyd. He was always learning, both an influence and an influencer. In 1955, he met pianist Bill Evans when they toured together as sidemen for clarinetist Jerry Wald. Five years later, Bill invited Paul and bassist Scott LaFaro to form his first groundbreaking trio. Best known for an extraordinary series of live recordings made at the Village Vanguard in 1961, the group redefined the jazz piano trio as a group of improvisers and equals. In the late 1960s, Paul began playing with pianist Keith Jarrett, first in a trio with bassist Charlie Haden, and then in Jarrett’s “American Quartet” with the addition of saxophonist Dewey Redman. They became lifelong friends.

Encouraged by Jarrett, who sold him his old piano, Paul began composing his own music in the early 1970s. Paul said of learning to play the piano, “I was in my 40s and felt like a school kid. With my piano books under my arm, once a month, I would walk the ten blocks to Deborah’s (Greene) for my lesson.” One day, Paul said, “I glanced down at my hands as I was playing and I didn’t recognize them. It was as if they were the hands of a stranger. They were playing the piano by themselves and playing quite well.”

Paul’s first album as a bandleader, Conception Vessel, was released in 1972 and marked the start of a 39-year relationship with the German label ECM. 1984’s It Should’ve Happened a Long Time Ago was Paul’s first record to feature his trio with tenor saxophonist Joe Lovano and guitarist Bill Frisell—a musical partnership that lasted for the rest of Paul’s life. Paul once summed up his career to that point in time: “I was Bill Evans drummer in the 1960s, Keith Jarrett’s drummer in the 1970s, and Paul Motian’s drummer in the 1980s.”

Over the next twenty years, Paul would revisit his roots in ways that were both new and familiar. In the early 1990s he formed The Electric Bebop Band, giving new life to old bop standards with an electrified lineup of two tenor saxophones, two guitars, electric bass and drums. During this time Paul also recorded the On Broadway series, a collection of standards from the Great American Songbook.

One of Paul’s less-appreciated roles was that of incubator of young talent. His bands served as launching pads for many young and then-unknown jazz performers including Joshua Redman, Chris Potter, Wolfgang Muthspiel and Kurt Rosenwinkel to name a few. Along with his music, this is his lasting legacy.

Always a maverick in his performances and compositions, the closest thing Paul had to a rule was, as he would often say, “Less is more.” His precision and economy of expression were matched by a commitment to creative exploration. He was a generous composer in that he was not threatened by, and in fact encouraged, creative freedom and spontaneity in the playing of his works. “I’m not exactly Cole Porter,” he once told Modern Drummer with typical modesty, “But I generally find what I’m going for.”

David McGuirl

Nephew

This biography is reprinted from the book “The Compositions of Paul Motian”.